Catching a bus is easy.

In a new city, with no sense of direction, and being fluent in 3 words of the local language, is not so straightforward.

The concierge at the hotel I was staying at told me how to get to my first landmark, Lucy, the first homo Sapien.

“Get the first bus to Kasanchis, get off, walk around the corner and find the bus to Sedis Kilo, get off at the big round-about then get another bus to Teardros”.

I wrote that down.

I was intending to find the Ethiopian Museum of history, The local University and a market that is apparently the biggest in Africa.

What I found instead was a city rich with the aroma of African life (figuratively speaking), a public transport system that works, and the remains of the first homosapien, Lucy.

But here’s the rub, buses in Addis Ababa run on a loose schedule and indicate their destination with squiggly Amharic writing on top. As the bus is pulling in to it’s stop a little guy jumps out while it’s still moving, swings on the sliding door as it opens, and yells out the location the mini-bus is going to.

He then lands on the ground with quick steps like the energiser bunny, slaps his hand on the roof to let his driver know to speed up again, because no-one jumped on board for the ride.

At the bus stop, around the corner from the hotel, I heard the following call from the door swinging energiser bunny: “alufkin lukwuddy Kasanchis” I repeated Kasanchis back to him and he nodded to get in.

In a mini bus designed for 11 people, I counted 17, with the call guy hanging out the door.

Along the way, holes the size of cricket pitches marked the road where enthusiastic city officials one day promised they would fill them in if they got elected, 15 or 20 other mini-buses scrambled for your service, and woman and children dodged and darted between all this.

In most cities, when you catch public transport you can bury your head in a book, look out the window, or zone out on your phone. We use it to fill a most basic need to get somewhere, to do something.

In most cities, when you catch public transport you can bury your head in a book, look out the window, or zone out on your phone. We use it to fill a most basic need to get somewhere, to do something.

In Addis Ababa – in the mini bus movement around town – you are heaving and breathing with your fellow man. If you fart, the bus will know about it. If you don’t like your seat, wait five minutes and someone will be on your lap, and if you don’t yell out to stop you get the city tour.

In most cities, there is some degree of public transport fraud; people scamming free rides, and governments spend millions trying to counter it.

In Addis, They’ve fixed that problem; they get a guy that can run as fast as a mini van who can hang off an open sliding door at 10 mile an hour. He sits at the door, so you either pay him, or you don’t get off.

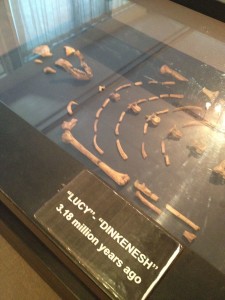

I paid the guy, and got off at the museum. Inside, the origins of the first humans stared back at me through cracked skulls, pieced together like dropped porcelain tea pots in your grandmas kitchen.

I left feeling accomplished that I’d made it this far. You know what it’s like; too long inside and you get mushy museum brain: A semi-lucid belief that you can read every place card and retain the information for no particular use at a later date.

I left feeling accomplished that I’d made it this far. You know what it’s like; too long inside and you get mushy museum brain: A semi-lucid belief that you can read every place card and retain the information for no particular use at a later date.

Back outside, about 20 buses blew by, all with the announcer guy swinging on the door calling out the location the bus was heading. All I could do was listen very closely for ‘Sedis Kilo’, my next stop.

I didn’t hear those words so I got in one going in the general direction I needed to, and just hoped for the best. I got lucky, and within 10 minutes I was in front of the sprawling grounds of the Addis University.

Inside the museum of ethnology I am walking through ancient Abyssinia like a 1960’s Ikea store; tribal pieces sat gathering dust, as though a high school art class had to store stuff in a spare room and no one came to collect it. There are 80 different languages in Ethiopia, it’s the home of Rastafarianism, the birthplace of coffee, and religions that scar your body.

Outside, numb from more museum brain, I borrowed the nearest guide from a couple of tourists with expensive camera’s around their neck, and he pointed in different directions and told me how to get the main market. All of which I was not following as he was telling me.

This time my bus trip was pot luck and I ended up in a street crammed with buildings hammered and nailed together by the sheer force of retail will. A dirt sidewalk underfoot reminded me that in Africa, it always seems like a work in progress.

Then something occurred to me that is at once enlightening as much as it is frightening: I hadn’t seen a white person all day and now here in this crowded market street, I was the minority.

It’s enlightening to feel this; like a switch had been flipped in my mind that was no longer just black and white, but human, yet different, but equal. And It’s frightening to experience this because the word ‘equal’ suggests I hadn’t thought that way previously. Unconscious racial bias had hit me right between the eyes.

I meditated on that mountain of a moment with the kind of crack coffee you can only get in Ethiopia. The buzz washed over me in the way coffee does when its a sunny Saturday at the market – even if it is the wrong one.

I meditated on that mountain of a moment with the kind of crack coffee you can only get in Ethiopia. The buzz washed over me in the way coffee does when its a sunny Saturday at the market – even if it is the wrong one.

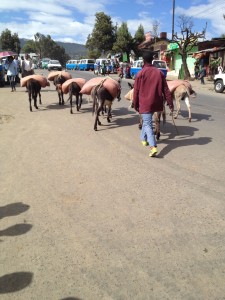

Around me a man selling goats moved his herd through the crowd, children looked at me like I was a science experiment, and the beaming smiles from people going about their life made me feel not so unique after all.

Getting back to the hotel was easy, I just had to retrace the buses back the way I came. If only navigating race relations where as easy as catching a bus back home in urban Addis Ababa.

Click here to see how I found my way around the North of Ethiopia…

This is such a great post! Thank you for sharing

Thanks so much Seema, it really is an amazing city, I love the people. Stay tuned for my adventures in the coutryside 🙂